PJ Goes From Peacock to Crow

PJ Goes From Peacock to Crow has to do with the much-discussed “new processing” of puerh. “New processing” makes puerh “ready” for drinking much earlier than customary. “Ready” means sweet. Old school processed offerings are not instantly sweet. In fact, a decade generally tends to be the benchmark for beginning to check in on the development of a conservatively processed and stored offering. Newly processed productions can be sweet the instant they hit the consumer market. Instantly sweet puerh enjoys broad appeal among the plug-and-play generation of tea drinkers.

Purists will say that this new processing is not puerh. It’s anyone’s guess how these avant-garde offerings will transform, a question of next to no importance for a plug-and-play tea drinker but central in the mind of the puerh collector. It’s worth noting that casting the differences as night and day between the two processing approaches mischaracterizes a technique involving creativity and skill. For certain, fast sugar expression comes at a cost to potential transformative complexity, but the same can be said of heavily stored puerhs where the heat and humidity burn away puerh’s underlying character in favour of putrefaction and dankness.

Since there there are no hard and fast standards for defining puerh beyond coming from Yunnan Province, tea makers are free to innovate or preserve tradition as they see fit. For puerh purists, the presence of green tea notes is an unacceptable breach of that which defines puerh. For others, who mainly drink very young productions from Western-facing vendors there is little frame of reference in the first place and often an inability to discern either. Oh well. The Puerh Junky doesn’t drink so many post-’14 productions, as even old school factories have joined the fray of new processing. However, sometimes the quest of the old-school factories to remain relevant gets interesting as it serves as a study to see how makers straddle the line between tradition and innovation.

Zhongcha’s Dance

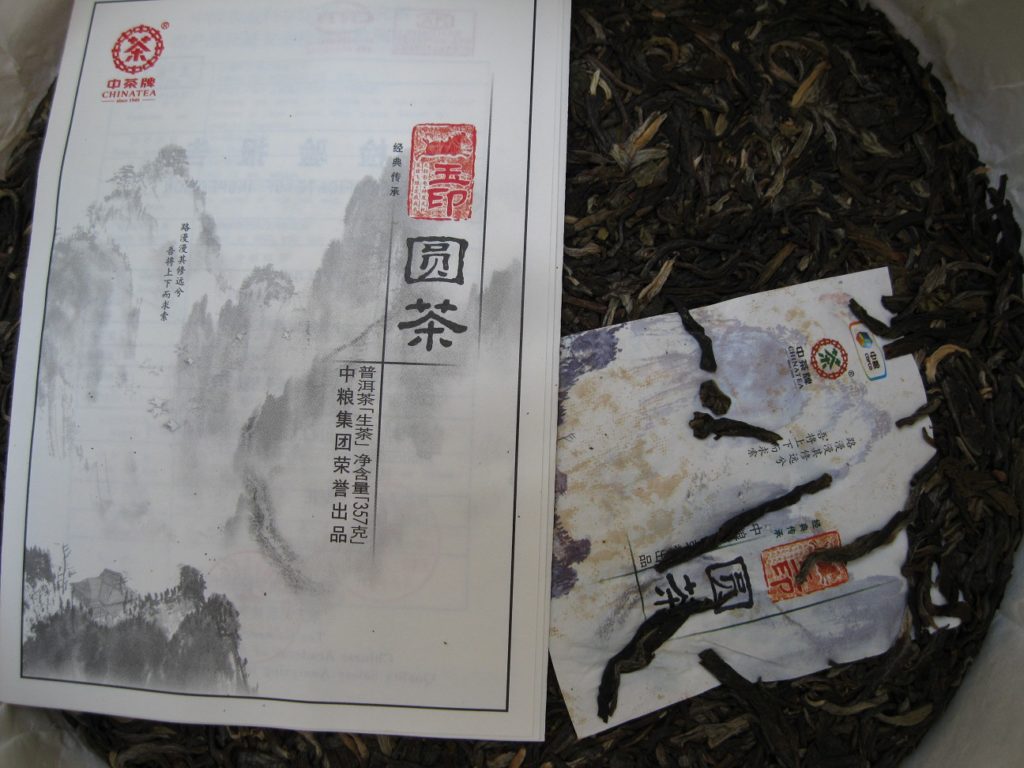

Zhongcha’s dance with innovation and tradition is worth visiting. On one end of the spectrum is the Jade Mark, acquired in ’17. The idea of it being newly processed never crossed my mind; the thought was that it hailed from Lincang, particularly the Bangdong, Bingdao area where there’s a reputation for stellar young tea. Up until that time, there’d been no run ins with sencha grade productions, so the sweetness was largely chalked up for terroir or pickings later in the season. Evidently, parts of Lincang have been executing the “new” shaqing for quite some time, so one doesn’t necessarily preclude the other.

In its nine years as of ’23, Jade Mark has continued to hold its own as a perfect example of either Lincang or “new processing” done very well and the reviews have always been unequivocally positive. As a recipe production, Zhongcha is not saying what it is. Be that as it may, as a a “gateway” puerh, Jade Mark is hard to beat, though its transformation potential remains entirely unknown. . . or nonexistent. Perhaps over the years it’s gotten sweeter, perhaps even more bitter, expressing more of true Bulang character than in its youth. It’s hard to say.

At the other end of the spectrum lies the Bulang Peacock from the same year. It started much more in the vein of a traditionally processed creation before manifesting an expression found in productions at least five years older. Vanilla and spice notes are rarely found in puerhs under eight and if they are then either the processing or storage has been ramped up. As of May ’23, BP appears to be moving on from its spicy and vanilla expression to something more camphorated. There are phases where it’s got a Lemony Snickets vibe going on, a Ricola taste with the vanilla only coming at the very front end. In contrast to the Jade Mark which has shown little change, Bulang Peacock is a constantly moving target. Such change is consistent with traditional processing, though everything seems to be happening at a quicker pace. The vanilla and spice still express depending on just how fast one goes from one infusion to the next and there’s some serious Bulang bitterness too. It’s captivating.

Xinghai Sweet Chariot?

During the Xinghai buying focus of 2022, Puerh Junky picked up a couple from ’15 and ’16 presumed to be newly processed. The ’16 Golden Peacock is the second Xinghai acquisition from that year. Here’s where the crow eating comes in because even though the grouchy junky (GJ) in me wants to hate on these insta-sweets, there’s no denying that Mme Zhang is very good, most capable at manipulating processing parameters in a way that gives the plug-and-play playa exactly what they want while not compromising the integrity of the material itself.

The Golden Peacock is sweet without being too sweet. There’s serious substance and depth that progressively unfolds with each infusion. What starts out as being possibly frilly frivolity moves into a very self-assured production. Bitterness fades quickly amidst omnipresent rock sugar sweetness and fruity note. The Golden Peacock isn’t a rookie puerh. It’s for those who like the boldness that Xinghai tends to offer, only at about ten years earlier than usual. It’s got fresh green vibrance, but there is no sencha or chlorophyll taste. Furthermore, there’s a noticeable fermentation aroma in the empty pitcher which promises that it will continue to transform.

Wrap-up

Aside from its controversy, new-school puerh processing exists along a continuum from traditional to borderline oolong and sencha. Consequently, old-school factories have many options for how they imagine the outcomes for an expanding “puerh” market. The case of Jade Mark demonstrates a puerh where potential for transformation plays a small role. By contrast, the Bulang Peacock, from the same year, has changed quite a lot. As of writing in May ’23, the Golden Peacock has changed relatively little. The ferment-y aroma is indicative of fairly traditional processing, while the sweetness is new-school all the way.