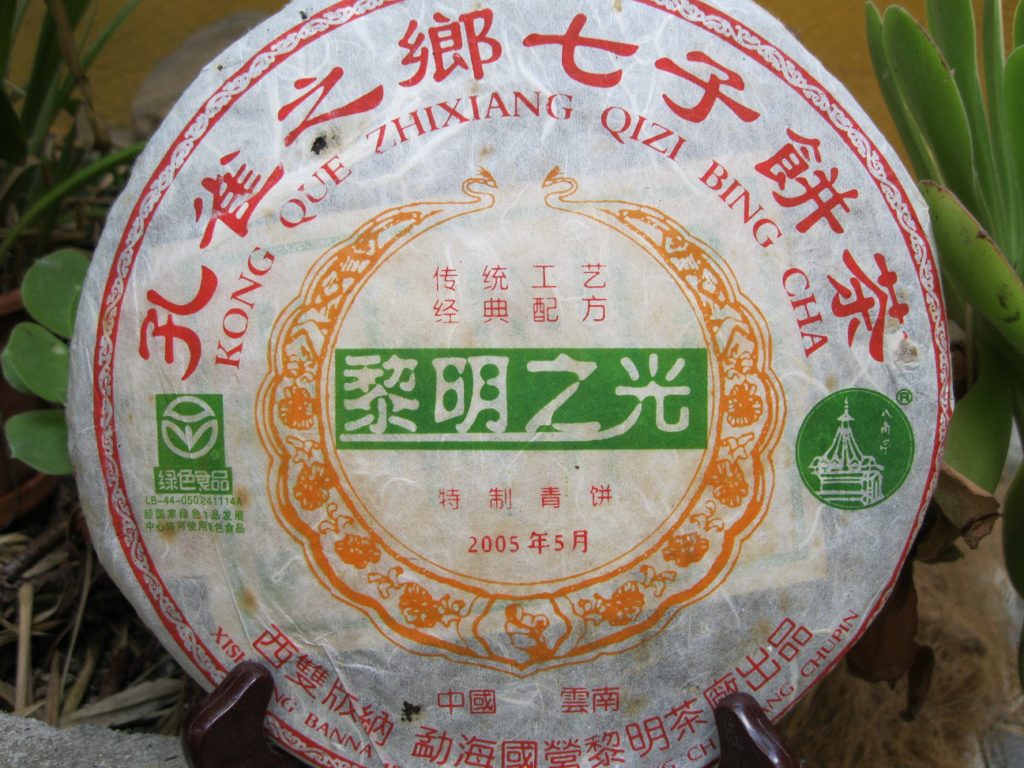

Visiting the 05 Peacock Puerh, LM

Visiting the ’05 Peacock Puerh, LM is not what I’d consider to be the most memorable experience. I’ve been sitting on this for about three years. It is tightly pressed early spring material from what seems to be Daxue Shan or Jingmai material, but this is only a guess.

A few weeks ago, I took it out of storage. I has a session with it about two weeks ago, where I noted strong green floral notes quite similar to 6FTM Lunar Series productions. However, the Monkey is far superior to this production. . . at least what I’ve tasted of it.

For starters the ’05 Peacock takes two infusions not counting the rinse to get beyond a storage taste, one that it had upon acquisition. None of the 6FTM Lunar Series have a stale storage vibe. The ’05 Monkey upon acquisition four years ago already had some distinctive spice notes. The ’05 Peacock is starting to develop a hint of petrol, but only for the second and third infusions.

The aftertaste of the ’05 Peacock is its greatest attribute. Usually by now, a production of this age has floral notes that are more chrysanthemum or dandelion in nature not orchid. In this regard it is quite similar to the Jingmai “003” from the same year, though the “003” has a young floral zing in the liquor as well as the aftertaste. In some regard, both possess aggressive attributes. The robustness of the ’05 Peacock’s liquor fades quickly before expressing Zen characteristics.

The body feel and effect of the Peacock is non-existent. The “003” and the Lunar Series are both far superior in this regard.

I’ve tasted the ’05 Peacock, LM on numerous occasions. I find it disappointing and overrated. The ’06 Peacock Brick, also by LM by contrast, is rich, spicy, and durable. They’re qualitatively different productions. The ’05 is decidedly spring tea, which is what accounts for it valuation. The Lunar Series and the “003” are two better productions that fall within the same floral class.