Milk Tea II

Milk Tea II follows upon the piece introducing milk tea’s inspiration. As promised, here’s the recipe. The creation has been an ever-evolving project. If you’re not playing with your food, then what are you doing?

Milk Tea– The Early Days

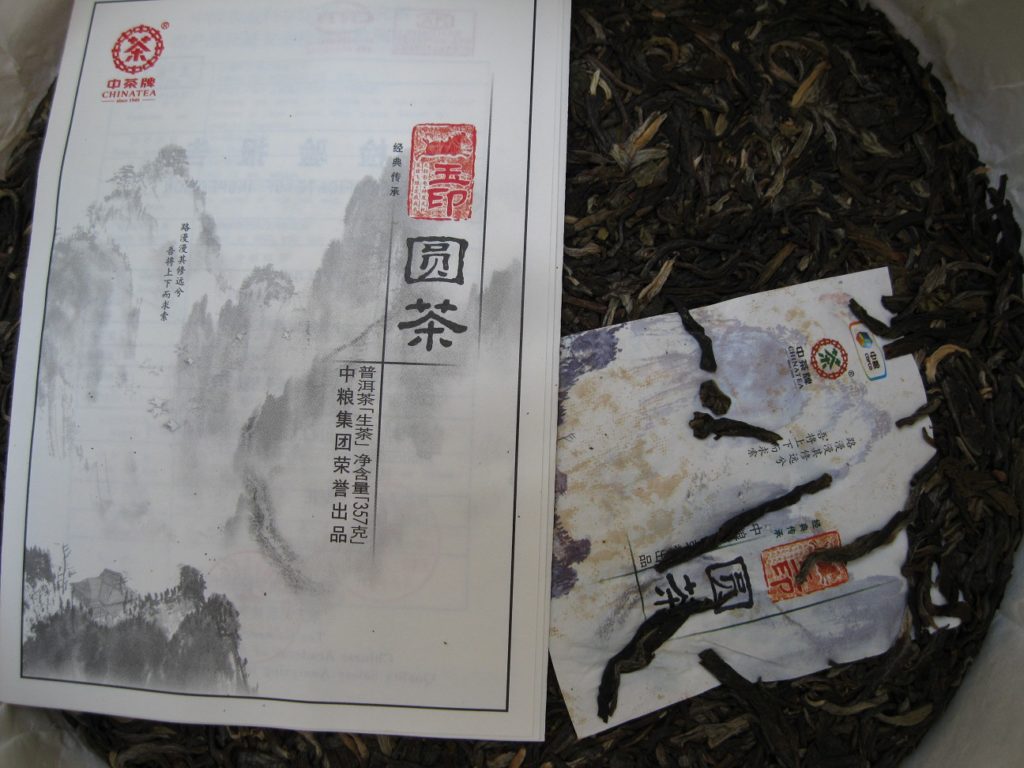

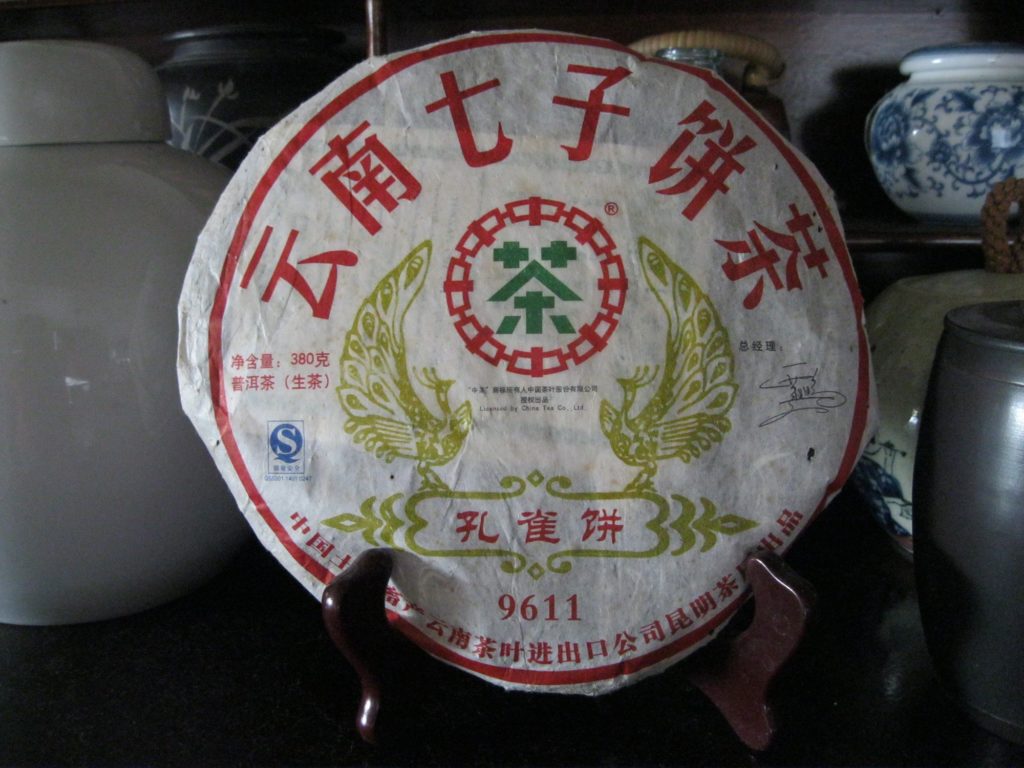

I’m not using milk, but coconut cream from Indonesia. Taking one from the West here, i.e., Mongolia and Tibet. . . some Indian accents clove, cinnamon, cardamom, even a bit o’ the Americas in terms of cacao. Just a pinch or two of these. At least a tablespoon of ghee and 2 teaspoons of grass-fed butter, 1/2 bonebroth. 13g ripe boiled in about 2litres water, along with 3g 山楂 (hawthorn) 1 piece 乌梅 (mumei). Started whizzing in blender for 4min. You have to remove all the chunky items before blending.

The main thought here was to add som citric acid via hawthorn and mumei to offset the effects of the oxalates in the puerh. Just ballpark the amount of cream.

Milk Tea– Traditionale, Sorta

Phase two witnessed elimination of the hawthorn and mumei in favour of half-and-half. Coconut cream works fabulously for creamy taste, but it doesn’t have any calcium, which is being used to bind with the oxalate. Citrate’s mechanism differs from calcium, as the former reduces oxalate concentration while the latter affects a calcium oxalate bond that passes through the system instead of bonding with endogenous (in the body) calcium.

Add coconut cream additionally if it suits personal preference. The cream factor along with butter is about 1/2 to 1 tea, with the other half being bone broth. There’s positively no need to be overly rigid in measuring. Just go by the colour of the brew and adjust accordingly.

Milk Tea– The Latest

The Mongolian milk tea makes use of millet. I’ve got this flour used to make an African polenta called “fufu,” which is a royal mess to prepare, so much so that it’s not getting used. This flour can be made from any grain I suppose, but I saw a plantain and a cocoyam type, purchasing both. “Cocoyam” is called something that sounds like “fish head” in Mandarin and is made in a few dim-sum dished, though much more common in Filipino and Hawaiian cuisine. I had to look up the alternate name that escaped me, “taro.” It happens to be the root of the Elephant Ear plant.

So far, only the plantain flour has joined the symphony of milk tea. I’ve read plantains are particularly high in oxalates. Evidently processing can affect oxalate content. Dunno of any differences when made into flour. Test findings seem to vary widely, so the reliability of any of the data is nil. In any event, the gist for using the flour was to add a cereal component to the tea like the Mongols. Two heaping tea spoons added after removal of the puerh and after the spices have had a few minutes to simmer and bone broth has been added. Seems like giving the flour a little bit of a cook is a good idea to transform the flour-y taste to something else, though I haven’t just adding in the blender. This addition kicks up the creamy thickness factor to a very high level.

Additionally, Chinese dates were added to the mix at the blending stage AFTER pitting. Five dates added a nice bit of sweetness without being too sweet. Chinese dates though sweet have about 1/4 the sweetness of dates from the desert of California or N. Africa. Also the taste profile is much more like a dried apple than whatever it is that palm dates taste like.

Wrapping Up

Milk tea comes to us by way of our Western friends in Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia. Each place varies how they make it. Recently, I saw the tea being made in Kazak- or Uzbekistan with green brick tea. This is how the Mongols seem to do it as well, though the Tibetans favour using ripe puerh. There also seems to be some seasonal variation, i.e., green for summer and more oxidized tea in the winter.

The focal point of the milk tea recipies offer above is first the ripe puer and second fat, usually in the form of cream and butter, though pork lard or beef tallow have been used quite often. Salt is not added in any of these recipes, as that is covered through use of boths that have already been salted, along with salted butter. The ratio is about 1 part puerh to one half broth and another half cream. The brew is not spiced heavily, though they add a nice balancing accent to the overall composition, just a pinch of clove, two pinches cinnamon, and three cardamom pods. Three pinches of cacao into the blender works dandy.

The milk free version with hawthorne and mumei is fine but requires a fair amount of brewing, while the milk version calls for adding after the tea has been brewed. Flour, I used plantain, adds a sinfully rich texture to brew. I wouldn’t avail myself of this option too often as it will tend to pique the appetite, while the flour-free creation works well as satisfactory meal in itself, even more so with the milk-free version. Finally, the sweet version can be used with any type of sweetner, palm dates, Chinese dates, raisins or even prunes. The concoction works best with what you already have on hand. There’s no need to go through any great extravagance, with the possible exception of the coconut cream.